The best view of the red carpet, I realized, was from above.

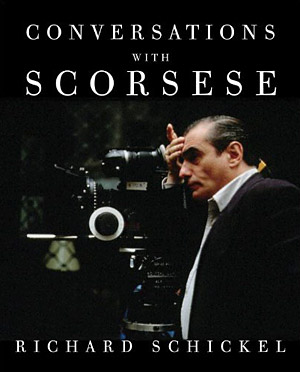

Browsing the bleachers a full hour before even the press arrived for The Rome Film Festival’s world premiere restoration of La Dolce Vita, I decided, finally, on a front row seat next to a shrunken woman of about seventy. Surrounded by blankets and snacks and cigarettes, she looked like she had been waiting all day. “No Scorsese?” she asked as I sat down beside her. (Scorsese was scheduled to introduce the film.) I told her it was still early. He’d be here. Disgusted, she threw up her hands. “No Scorsese, no cinema!” I’m not quite sure I agree, but it’s hard to disagree.

Fifty years after La Dolce Vita’s original release, the film has been restored from its original widescreen negative for the clean up of a lifetime. The premiere, which was itself a thing out of Fellini – from Nino Rota on the loudspeakers to the paparazzi on the floor – saw an avalanche of beautiful stars that all looked liked twins, save for one. Early in the parade, before things got too frenzied, a black car stopped as close to the carpet as it possibly could, a policeman flew to the door, opened it (slowly), reached in, and out came a cane, a foot, and then the rest of Anita Ekberg. The place went nuts.

As the new stars began to appear, with their smiles and waves and tastefully torn clothing, the mighty Ekberg limped wryly toward the press line, accentuating every labored step with a grande sigh. She had a lot of carpet to walk, and watching her fight it, prodding it with her cane and laughing all the while was a thrill even the most immaculately restored La Dolce Vita would not likely upstage. Moreover, Ekberg was the only woman on the red carpet with a purse slung over her shoulder, as if she had just came from lunch. How could you not love that?

I moved inside the theater to watch the rest of the arrivals on the big screen, in close up. There I rediscovered Ekberg’s entire face. Tickled, I found her jack-o-lantern smile, enormous eyes, and high-pointed eyebrows told of a darker, wittier person than I remembered from the movies. But I have a good defense: after the Trevi Fountain scene, all you can do is remember the Trevi Fountain scene.

The camera then drifted away from Anita (what would have Fellini have done with a Steadicam?) to Scorsese, and the entire theater erupted in applause and cheers, and then immediately hushed to hear what he had to say. At that moment someone behind me whispered, “You don’t have to be tall to be big.” In other words, No Scorsese, no cinema.

Once the little giant entered the building, things started to move quickly. There were a few introductions and some clips before Anita Ekberg was brought out on stage (with purse) to remember the filming, which she did with sardonic glee. I’m not sure, but she may have cackled. In fact, Ekberg got so gleeful she didn’t even see the cortege of stagehands that had gathered to signal her time was up. So she went on, gleefully, and as her enthusiasm grew, they moved closer, until finally the cluster was on stage, practically standing beside her. Even then she didn’t see them. So deep was her Fellini trance, they had to literally, almost physically, interrupt her sentence to bring her back to the present. It was glorious.

Then Scorsese. Watching La Dolce Vita, he said, is like the dream sequence – Guido freefalling – that opens 8 ½. “You feel like you’re flying,” he said. “At times it’s frightening or even terrifying. But at the same time it’s liberating.” In other words, no Fellini, no cinema.