Theresa Russell is attracted to the very things that repel most actors.

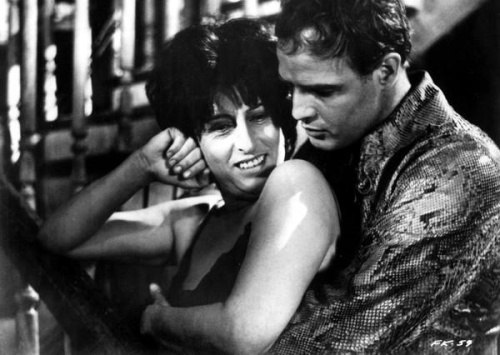

In 1976’s The Last Tycoon, her first movie (and Elia Kazan’s last), she is unafraid of seeming to do very little. Young actresses like to show you they can act by really “acting,” but Russell, at only eighteen, knows what it means to be simple—and Kazan knows she knows. His close-ups foreground a girl of California gold darkened by knowing eyes. It’s like two different people looking at you through a single face. And just when you think she can’t possibly be that smart or strong, her voice breaks in the middle of a line like Barbara Stanwyck’s when she looks at Fred MacMurray at the end of Double Indemnity, and we forgive her everything, take the blame, and sign up for more (almost). In Bad Timing (1980), she works from the epicenter of a carnal earthquake and never once has to brace herself on secondhand, movie sexuality. Her moves are all her own. The result is something like Brando in Last Tango in Paris—too real to watch and not watch. There again you see what Kazan saw: the wilderness inside. Nicolas Roeg, her husband-director, saw it too. In (1985’s) Insignificance, their third collaboration, she plays Marilyn Monroe.

Sam Wasson: You’ve told this casting-couch story about Sam Spiegel, producer of The Last Tycoon. In the versions I’ve read, he basically threatens to destroy your career if you don’t sleep with him. You’re eighteen or so, without a single credit, and he’s this titanic power—and you reject him. With that rejection, it’s like you’re rejecting—I hate to say it—the Hollywood way.

Theresa Russell: I didn’t have anything to compare it to other than I knew that I didn’t . . .

SW: You weren’t going there.

TR: Yeah, exactly. If it meant the end of my career, then I don’t have a career. Okay. I always had other options. I’m good with animals. I had other things I wanted to do. I had to take that gamble because there was no choice, basically, in my mind. My boyfriend at that time, my first love—he was a primal therapist—he helped me a lot during that.

SW: This story about Spiegel combined with the movies you’ve picked all point to a quality you have, on-screen and off—zero tolerance for bullshit. Do you have any theories about how you came to have that kind of self-possession?

TR: No, I really don’t. I think I was born that way, basically. It’s slight madness, perhaps. My attitude about life in general has always been a little off, I suppose, compared to other people. It seems like the older I get, anyway, that’s true. [Laughs] But later on, I had to do shit things just to pay the bills and pay school fees, which was hard, but in some ways it taught me some good things too.

SW: To what extent do you think having a relationship with a primal scream therapist played a part in—

TR: In acting? [Laughs] Oh . . . I think I was that way anyway, but that did help in my acting, I have to say. Doing that kind of self-exploratory stuff. I think it helped me be less afraid in my work. Not necessarily in my life. I mean, my dad left at an early age, and I left home at sixteen.

SW: In your mind, does the primal scream connect to the Method?

TR: I think so, yeah. In that regard it correlated completely with my training. And it just made acting less scary. A lot of actors are afraid to go into those darker places of personal experience. Early memories, traumatic situations. That pain. So in that way, the primal scream showed me I could go there and come out okay.

SW: Let’s talk a little about Insignificance. Was this a part that immediately jumped at you?

TR: Actually, originally I turned it down. Here’s what happened. [Producer] Alexander Stewart kind of approached me before he even approached Nic [Roeg] to do it. I don’t know if Nic will even remember that, because he kind of rearranges history sometimes—like his movies [Laughs]—but that is in fact how it was. Maybe he wanted Nic all along, I don’t know, but he came in that way. I knew the writer of the play [Terry Johnson] didn’t want me to do it. He wanted Judy Davis, who had done the play in London. I think they were kind of an item for a while. So he was not happy with me doing it. Also, there had been a slew of Marilyn things going on, and Madonna was in her Marilyn phase, and I was just like, Oh, God, I just can’t even think of going there, it’s just too silly. I just don’t want to.

SW: What changed?

TR: I loved the play. I just thought it was a terrific play. But to be Marilyn seemed so daunting, and I didn’t know how I would begin to go there in a way that wasn’t a caricature—so obviously it was just easier to say no! But then when Nic wanted to do it, that’s when it got to another level.

There’s more. Read on at Criterion.