This week, as the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s celebrates its fiftieth anniversary, generations of fans old and new will amble up Fifth Avenue, press their noses to the shiny windows on 57th and remember their first times.

It will be a bittersweet day for me, however.

Sweet for all the right reasons, bitter because the age of the grown up Hollywood comedy is long behind us. Mind you, this isn’t nostalgia, it’s arithmetic: the people making the movies have changed and so have the people they’re making them for.

As a former seven to twelve year-old, I was a huge fan of sameness. That was the great thing about The Kids Menu. No matter where your parents took you, it was always the same. Pizza, pasta, grilled cheese, simple, familiar, benign. The perfect speed for a young person not ready for the Big Out There. That’s Hollywood today.

No offense to pizza, but this is tragic for those of us care to enjoy a piece of arugula from time to time.

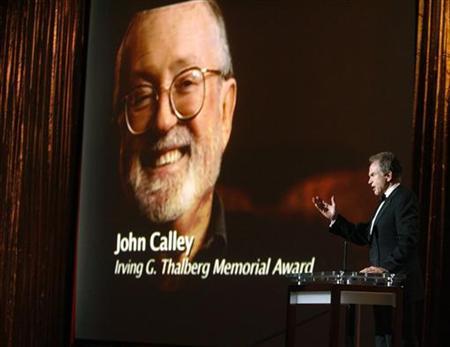

Even more tragic for those of us who were eating off The Kids Menu when the likes of John Calley, the great and beloved studio chief who died three weeks ago, was in the kitchen.

A true master of the art of commercial art, Calley oversaw a successful series of highly diversified films, ranging honorably from healthy dreck to serious grown-up fare. For every meandering, money-grabbing Da Vinci Code on his tremendous resume, there was challenging, immortal A Clockwork Orange. For every dollar earned, in other words, there was a risk taken.

The very beautiful thing about this era of not-tool-long-ago is Calley wasn’t alone. There were others making money, making art. Fox’s Alan Ladd Jr. said yes to Star Wars and Harry and Tonto, a movie about an old guy and a cat; United-Artists’s David Picker agreed to Dr. No and Lenny, a movie about the price of making tough art; Paramount’s Richard Shepherd green-lit The Towering Inferno and Breakfast at Tiffany’s, a movie about free love before the term even existed.

Alas, Shepherd wouldn’t get far with Breakfast at Tiffany’s today, at least not if he were making the grown up version we know and love. Out would go the subtle innuendo, European couture, moral ambiguity, and brilliant counterpoint casting of its good-girl star in a bad-girl part, and in their place, rim-shot jokes, the latest fashion trend, explicit messages, and safe, dependable typecasting. In other words, today’s Tiffany’s would be a film suited to the mundane demands of Hollywood’s most admiring customers: kids. Theirs is mainstream film’s greatest love affair.

No business likes risk, and lucky for Hollywood, younger audiences, prone to the pressures of “cool” and partial to formula, are about as risk-free as a demographic gets. They know what they like and they like what they know. Thus are the young supplied with sequels, franchises, remakes, and movies named after board games (Battleship will be released in 2012). Anything to serialize what has already been serialized before.

To be fair, this isn’t an entirely new phenomenon. As far back as Hollywood’s first star, movies have tried to homogenize their product in a way that was mutually beneficial for both business and audiences.

If they like Cary Grant, the thinking went, give them Cary Grant movies. If they like Marilyn Monroe, maybe they’ll go for Kim Novak. Sometimes it even turned out well. But not anymore.

The very big, very small difference between then and now is back then, novelty had a commercial ring to it. Mixing proven types with risky, unproven material, like Audrey Hepburn (a franchise) plus Truman Capote’s (challenging, naughty) Breakfast at Tiffany’s, was in 1961 an attention-grabbing combination. A gamble yes, but a gamble bold enough to win big: revoking homogeny, Richard Shepherd’s film was bigger than any single demographic alone. That meant kids, grown-ups, Hepburn’s fans, and Capote-lovers all had something to look forward to.

And thank goodness: Without that lucrative roll of the dice, the film would be little more than a serialized rehash of Audrey’s persona and hardly worth remembering today. Even if the movie failed, it would be worth remembering because, thanks to Shepherd, Breakfast at Tiffany’s had prestige out of the gate. It pandered up.

The Sex Pistols’ late manager Malcolm McLaren observed ours was a karaoke world, an ersatz society. As long as his statement applies to Hollywood, and it does, we’ll never see the likes of an Audrey Hepburn in a Breakfast at Tiffany’s ever again.