Flipping through the index in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls — a book about the rampage of sex, drugs and revolution in Seventies Hollywood and Hollywood in the seventies — one discovers that “Mazursky, Paul” has only two page numbers after it. (Scorsese alone takes up six lines.)

At the time, Mazursky’s status as one of the decade’s reigning directors was an item of popular and critical consensus, but by the early nineties, the tides had turned. The Pickle (1993) was panned, and Mazursky’s subsequent efforts, though intermittently wonderful, did not live up to the work of his New Hollywood golden age. These days it seems like many cinephiles and even some critics have simply forgotten Mazursky’s films, full stop.

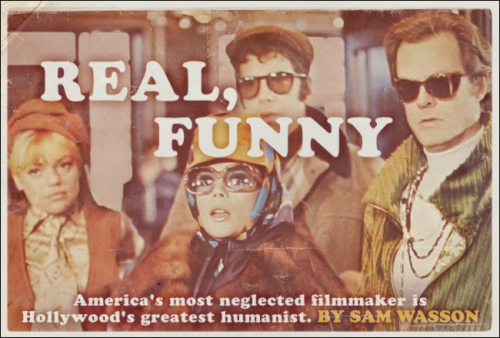

But back then (way back), in the American cinema’s most formidable post-war decade, Mazursky was untouchable. So much so that Time magazine critic and Film Comment Editor Richard Corliss could confidently predict:

Paul Mazursky is likely to be remembered as the filmmaker of the seventies. No screenwriter has probed so deep under the pampered skin of this fascinating, maligned decade; no director has so successfully mined it for home-truth human revelations…. Mazursky has created a body of work unmatched in contemporary American cinema for its originality and cohesiveness.

Mazursky’s pictures were explicitly, almost aggressively, enmeshed in the here and now (or from the vantage of decades passed, the then and there). Remember the psychedelic brownies? The suburban orgies? Remember the gurus, the shrinks, and the Rodeo Drive fetishists? They’re all there. Chronicling these shifts in the cultural ethos, Mazursky has preserved the changing passions of the American middle class in a kind of comic formaldehyde. The films were prescient, honest, and always hilarious.

Nearly forty at the time of his directorial debut, Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969), Mazursky was some ten years older than the fresh batch of younger iconoclast directors. That fact understandably clashed with the then-popular image of directors as studio-lot rebels and insurgents of style. Mazursky, by comparison, seemed like an old-fashioned romantic and unreconstructed classicist. Like Frank Capra, he had an open heart but a satirical squint. Like Jean Renoir, he never let jokes get between him and the hard truths of his characters. And unlike most New Hollywood filmmakers, Paul Mazursky, part hippie, part father, had perspective andtendress. There was no other Hollywood writer/director with such a generous admiration of human foible, no other American auteur so shrewdly attuned to the cockeyed truths of how we love.

How could such an accomplished film-maker have slipped by?

Please continue reading reading excerpts from my new book, Paul on Mazursky, at Altscreen.