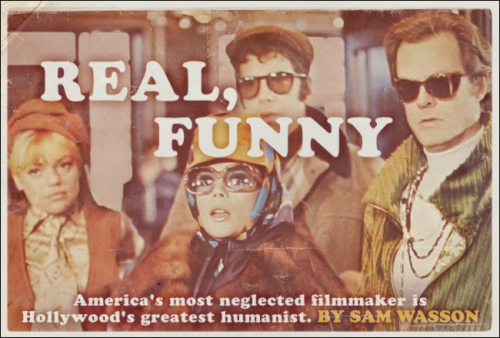

Chekhov is about time—passing it, mostly.

He never cuts to the chase, only hints at it coming from a long way off. Then there’s the waiting, the sitting around and rattling on; it’s old-country mumblecore. André Gregory’s workshop production of Uncle Vanya, performed sporadically through the early nineties for audiences of a dozen or so lucky guests at a time, got that just right. As delivered by Wallace Shawn and friends, Chekhov’s dialogue was stripped of formality, stripped of pomp, played at the level of room tone at 10 p.m., after the dishes are cleared. It took them years to get there—years of letting the time pass and waiting for something to happen. Instead of having his actors master Chekhov’s people with strong preconceived intentions, Gregory reversed the flow, allowing the characters the osmosis time to master his actors. Director Louis Malle was one of the lucky few to see Gregory’s Uncle Vanya. And he wanted to film it. But how would he touch the bubble without breaking it? It was a tiptoe situation, like dismantling a house of cards and putting it back together again, and it was up to Louis Malle and cinematographer Declan Quinn—further constrained by budget, time, and the crumbling New Amsterdam Theatre—to figure out. Here, Quinn reveals how a single camera, a few bungee cords, and some very long takes combined to bring about the ghost art of minimum impact filming, and make Uncle Vanya into Vanya on 42nd Street.

Sam Wasson: How did you get involved with Vanya on 42nd Street?

Declan Quinn: Fred Berner and Alysse Bezahler, the producers, introduced me to Louis. That was it, really. Obviously, it was very exciting for me to be meeting with Louis Malle. I was a big fan of his films. That first meeting may even have been a phone call. We discussed a fairly loose approach to the thing—that he’d like to run the scenes long and shoot Super 16, and that it was very low-budget. We had to approach it in very broad strokes in terms of lighting and camera. He said we were going to be shooting in this old abandoned theater, a decadent space for a play about decadent attitudes. He gave me some ideas about a natural soft look. We went into prep fairly quickly.

SW: With a space like that—a landmark literally falling apart around you—how free could you be?

DQ: We really couldn’t attach to any walls or anything, so we had to be freestanding with our lights. We would up-light certain theatrical features, certain plasterwork and interesting details in the ceiling or along the columns around the stage. Lights were on the floor for those kinds of things, on dimmers. And then for the actors, we tended to work on the floor more kind of movie-style, where we might have a 12×12 or 8×8 diffusion with a light pushing through it or a light bouncing, and then some bigger cloths to shape the light a little bit. The good thing was we had enough space to get back twenty feet or so and create a nice, soft, general light for scenes like the beginning of the first act, where it’s supposed to be dayish. And then when we got in around the table, it became a little more enclosed, and the lighting became more closed, as if it’s coming from lanterns, from practicals. The New Amsterdam was just a wreck at the time and had been leaking for years, as we discover in the beginning of the film. It was cold and damp in that theater, a real chill that gets into your bones after a while, but it was an exciting place to work. Originally, we wanted to work up on the stage, because it would have given us a bigger backdrop, but we weren’t allowed there because there was a lot of ironwork suspended above that wasn’t safe. God forbid anything fell we didn’t want to be under it. So we staged it over the orchestra pit and what would have been the first bank of seating on the main floor. [Production designer] Eugene Lee built a bridge across the orchestra pit so that we could make entrances and exits from the stage to the area we were working in. In fact, when we started shooting, Disney came in to take photographs and start planning the refurbishing of the theater.

SW: As the play goes on, you begin to lose a sense of the theater. It gradually disappears until you’re in a kind of limbo with the actors.

DQ: We wanted to create a more neutral space, more existential, in the void.

SW: The transitions are so elegant, often imperceptible, starting with the actors meeting out on 42nd Street and following them into the lobby, into the theater, and then suddenly you cut behind them to give us the audience, and suddenly you realize the play’s on. It’s beautiful.

DQ: That was Louis’ masterful vision of it, a conscious thing on Louis’ part. He built all that into the dialogue before the play starts. All that talk about how tired they are, so the tone wasn’t broken. He wanted you to see how contemporary Vanya was. I think he was able to make that point really well by surprising us. There’s hardly any difference between 1990 or whenever we shot it and a hundred years earlier, in Russia.

SW: All that prerehearsal talk, was that ever put down on a page?

DQ: I don’t know for sure. I know they certainly talked about it before, but we didn’t shoot many takes of that kind of stuff. It was on the fly. We were like, “Oh, let’s follow Wally on that one” or “Let’s follow Julianne [Moore]” on that one, so I don’t remember there being a script for any of that stuff—of course, until the play starts.

SW: The long takes really bring out the collaborative nature of the production.

DQ: A 16-mil camera can hold a little over ten minutes of film, so the takes would be usually a full mag, ten minutes, so we would back up and maybe overlap something if we were moving on. Say, if we wanted to pick up five minutes into the second act, we’d probably back up two or three minutes to get up to speed and then run seven or eight minutes until the film ran out.

SW: Was the decision to go with Super 16 mostly practical?

DQ: Yeah, I think that was one good reason. You had a lighter, more agile camera that could do ten minutes per load. You could do the same with 35, but it would be two to three more times expensive for the film and the camera would require a heavier support, probably a dolly or a crane, and it just wasn’t that kind of film. We thought if we could make it handheld and kind of looser and not feel too rehearsed, it would serve the project better. And I also discovered about a year or two before a way to hang the camera off elastic bands—like a long, long bungee cord—that gave a weightlessness to the camera and allowed me to go for ten minutes of moving the camera pretty freely without getting too shaky.

SW: Bungee cord?

DQ: Basically, a couple years earlier, my key grip, Kevin Smyth, had worked on a music video with a Japanese DP. He came to me one day and said, “I gotta show you something.” He was using fifty feet of surgical tubing, which is what doctors in the hospitals use for clearing people’s stomachs and stuff like that, basically a latex, thick-walled tube that has an amazing amount of elasticity. Usually I’ll double or triple it for a 16-millimeter camera and then make it as long as possible. If it’s fifty feet long, it’s more like a hundred and fifty feet when it’s elasticized. Our key grip was able to get a piece of truss and arm it over the space we were working in and counterweight it at the back, and we were able to hang the elastic over front. We just used a carabiner to attach the tubing to the handle of the camera. So we had maybe a twenty-foot drop from the truss to where the camera was hanging. I’ve used it ever since.

The interview continues at Criterion.com